by CHRIS PATSILELIS Houston Chronicle Aug. 12, 2002

INTO TIBET: The CIA's First Atomic Spy and His Secret Expedition to Lhasa.

By Thomas Laird. Grove, $26; 364 pp.

IN the immediate post-World War II period the Soviet Union expanded into Eastern Europe, and its scientists were working hard at building an atomic bomb. Mao Tse-tung's Communist People's Army had Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist forces on the run. With the free world looking on these events in awe and fear, America's new CIA, formerly the wartime Office of Strategic Services, galvanized itself to find ways to stop the ominous spread of communism.

In his revealing new book Into Tibet, American photographer and Asiaweek journalist Thomas Laird examines a little-known incident in the Cold War and thereby throws a brilliant light upon the character of America's intelligence and foreign-policy organizations of the time.

Both Douglas Mackiernan and Frank Bessac, Laird tells us, had worked with different military intelligence units in China during World War II. Both had become CIA agents when that organization was formed in 1947.

Mackiernan, a suave lady's man in his 30s, had done meteorological research and was a long-standing ham-radio operator. Before he was 30 he had been chief of the Army Air Corps Cryptoanalysis Section in Washington during the war.

By war's end he had been sent to China, where U.S. bomber pilots had depended on his weather data, which he decoded from Soviet broadcasts, to bomb Tokyo and Hiroshima. From 1947 to '49 he had investigated the Soviet mining of uranium in northern China and had secretly planted electronic sensors to detect the Soviets' first atomic blast Aug. 29, 1949, in Kazakhstan.

Frank Bessac, in his mid-20s at the end of World War II, had been scheduled for what was viewed as a suicidal OSS mission behind Japanese lines in southern China. But the two atomic bombs ended the war. Fluent in Chinese and steeped in the country's culture, Bessac, in 1946, was stationed by the OSS in northern China near the border of Mongolia, where an inner-Asian war was brewing.

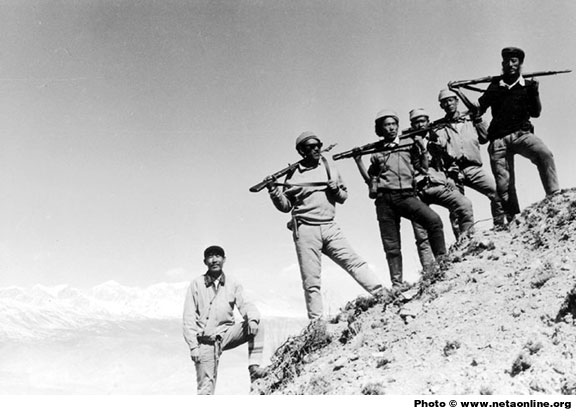

The author, who has lived many years in Nepal, recounts how the careers of these two intrepid CIA agents converged when they were sent on a covert mission in autumn 1949 to negotiate a secret arms deal with Tibet, a country then being threatened by Chinese invasion. The mission was approved by the State Department, among others by Undersecretary of State Dean Rusk, who would approve the same type of covert aid to fight communists in South Vietnam 20 years later.

Emphasizing the United States' political anxieties about the Soviet Union's first atomic blast and about Mao's imminent communist takeover of China, the author details the pair's 2,000-mile, one-year secret trek across China to remote, fabled Lhasa, capital of Tibet, to visit the Dalai Lama and to offer the Tibetan leader U.S. arms to fight China.

On April 29, 1950, the small party (three noncommunist Russians accompanied them) was attacked by Tibetan guards who had not been notified of their coming. Mackiernan and two Russians were shot dead at point-blank range and then beheaded. Bessac and one wounded Russian were captured and taken to Lhasa, which Laird describes as "floating like a vision above the emerald green barley fields."

The Tibetans, acknowledging their grievous error in shooting Mackiernan and the two Russians, allowed Bessac and his companion to freely travel about Lhasa. Bessac set about contacting Tibetan government officials to discuss the covert supplying of U.S. weapons to Tibet. A month later Bessac left Lhasa with a written request from the Tibetans for arms in order to repel the imminent Chinese invasion.

But before our State Department or CIA could act, Chinese troops, in October, moved into the country.

Laird writes that in 1950 "America denied that there were any American agents in Tibet prior to the invasion." The author maintains, therefore, that his book "proves, for the first time, that not only were Americans in Tibet, but that secret agents ... worked actively to send military aid to the Tibetans prior to the Chinese invasion ... that the highest levels of the US government were involved in that planning ... and how American actions may have hastened the Chinese invasion of Tibet."

To be sure, these are strong charges. And Laird admits that much of his investigation, other than interviews with eyewitnesses and research at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., was hampered by the solid brick wall of CIA classified information.

But he feels certain about the conclusions of his research and of the U.S. government's cover-up. "For fifty years," the author complains, "great pains were taken ... to conceal what truly happened before, during, and after this expedition."

Although Laird should have centered his story more on the expedition itself rather than repeatedly shifting from the story to historical explanations, it is still a fascinating, groundbreaking work on a controversial subject about which few readers will be familiar. Packed with vital new information and insights, Into Tibet fills a blank space in the hidden history of the Cold War.

Chris Patsilelis is a reviewer in Hamden, Conn.